Genders and world enders in

The Power Fantasy

I’m really enjoying the Power Fantasy by Kieron Gillen and Caspar Wijngaard, and it has all the makings of an all time favourite serial for me if it wasn’t for one thing that keeps nagging at me.

For those who don’t know the comic, here’s the pitch:

“Superpowered.” You have certain preconceptions. They’re incorrect. Here, that word has a specific technical definition. Namely, “any individual with the destructive capacity of the nuclear arsenal of the USA.”

There are six such people on Earth. The planet’s survival relies on them never coming into conflict.

The first issue is available for free here.

The Power Fantasy is a story that is fully occupied with power, ethics, morality, and people. The surviving characters are all to some extent sympathetic and reasonable (something of a survivorship bias: if they weren’t, one of the other Superpowers would have removed them before they became unchallengeable, or the world would have already ended). All of them have played or are playing their part in staving off a final, unsurvivable apocalypse, and all of them are constantly having to navigate their relationship to power, for the benefit of their personal relationships but also for the benefit of the world at large.

The fact that so much of the comic is driven by people with basically good intentions is part of what makes it so compelling. I might think Magus is driving some dangerous developments in the comic and will ultimately need to be stopped by someone, but I don’t think he’s wrong to fear Etienne. I might object to Etienne’s methods, but I can’t deny that the reasoning behind them makes a good amount of sense.

So, where does my frustration with the comic come from?

To the surprise of absolutely nobody who knows me: it’s the gender angle.

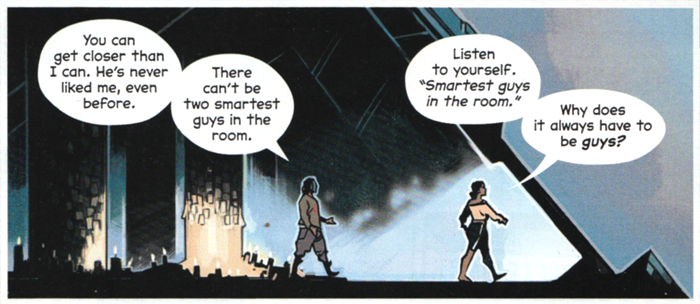

Out of six characters - three men, three women - we have two male masterminds (Etienne, the telepath, and Magus, the occultist), and two women whose mental health issues threaten to bring about the end of the world (Masumi, whose negative emotions and dissociations threaten to summon a kaiju, and Eliza, who has damned her own soul to Hell for world-saving power, and may do something terrible if she ever fully understands the price she has paid). And while Etienne observes that "in a long enough timeframe, any human with our level of power is Masumi", this acknowledgement is a bandaid at best; under the current status quo, none of the male Superpowers are actively in danger of suffering a mental break.

That the third woman in the cast, Valentina, is a genderbent Superman analogue (a fun twist in its own way) doesn’t do much to mitigate this: it means the only ‘stable’ female Superpower is literally a purehearted angel, which isn’t exactly a revolutionary new female archetype either.1

That all said: Gillen’s work on other teams (I’m still yet to catch up on Wijngaard’s) and the varied and dynamic roles that women occupy in the likes of DIE and WicDiv made me want to dig into the matter a little deeper than I might otherwise. And true enough, there’s a decent amount to mine here, especially when we consider what would be lost if some of the characters had their genders changed.

To start with, Masumi’s plotline would read very differently. The whole world bending to appease, flatter, and manage the emotional wellbeing of a man for the fear he’ll snap and kill everyone is perhaps a little too close to real life, and reflects a lot of real world dynamics that end in women dying. Certainly, it would be harder to emphasise how tragic the situation is from Masumi’s side, as her girlfriend Isabella’s position - even if she too had her gender changed - immediately becomes more obviously abusive in this context.

Which I do think would be a shame. For me, the reason I find Masumi’s situation so compelling, and the reason I’m rooting for her and Isabella even despite it all, is that as narcissistic as she may be - and despite at least one dangerous reaction to being publicly humiliated, albeit at a time of high stress - she does genuinely think the world of Isabella, value her honesty, understand that she is in a difficult position, and want to do right by her. The fact that the power dynamics at play make that nearly impossible is part of what the makes the situation so tragic.

I think it would be easier to have a male version of Eliza, but not without tweaks; her backstory is also fiercely informed by her gender. The inciting incident for her entire descent to hell is a glass-ceiling situation of sorts, a male leader excluding a woman from the seat of power partially because of his attraction to her. Jacky's refusal to act on his feelings is positioned by Dev as demonstrating his commitment to his values, but the comic is quick to emphasise the injustice to Eliza. Perhaps she was hellbound from the start, but would she really have sold her soul if she was one of the precious few trusted with the knowledge and the duty to guard it, rather than stealing pieces of the puzzle from the outside?

And then there’s Etienne’s involvement. For both women, he has stepped in and set himself up as the manager of their emotional state; he’s taken away truth from both of them, having either decided that they can’t handle it, or (more charitably) that he can’t risk finding out if they can.

This decision reflects a patriarchal attitude that threatens to blow up in everyone’s face. In Masumi’s case, she’s already demonstrated in Issue 9 that she has more resilience than he gives her credit for, and in a way, his careful management of her life is harshly limiting her ability to further develop that resilience. (The fact that the most positive relationship of her life - the one relationship where she gets some slivers of honesty and genuine care - is with a woman is perhaps not a coincidence.)

With Eliza, it’s even more audacious. It’s suggested that Etienne - having become convinced of the danger of Eliza undergoing a mental break through a conversation with Magus - decided to trick her into thinking that she was hearing affirmations directly from God less than a week after her descent. She’s been trapped in the cycle of confession and penitence ever since, ten years with not even a hint of moving on - and Etienne is almost certainly the one to blame.

For all that he might describing his actions as ‘sooth[ing] her’, what he has done is well beyond simply giving her a sliver of hope that she might be saved from Hell; he’s making her think she has a direct line to God, and in doing so, actively feeds into her biggest flaw, her self-identified sin: pride. She dismisses others’ input, convinced of her own righteousness; the monuments to her ‘penitence’ are huge and grandiose; she gloats to Valentina that she’s closer to God than her. And her smile when ‘God’ responds to her voiced fears seems filled more with satisfaction than with relief.

Why would she try to move on or change anything about how she lives her life, when she’s being continually, directly validated by the object of her lifelong worship?

Etienne insists that it’s unethical to leave things up to ‘coin flips’, but instead he has set up a house of cards that seem poised to fall the moment that Eliza tries praying in a space where his influence doesn’t reach2 - for example, within the sealed Pyramid, or if she accepts one of Magus’ masks. The realisation of his interference would be bad for anyone, but it will be spectacularly bad for Eliza, for whom pride is such a dominating quality. Masumi’s reaction to an art critic's fawning and fake review was one thing; Eliza discovering that she has been manipulated by Etienne (and that Valentina, who she gloated to, was in on it) feels like the kind of realisation that could easily wipe out another continent.

And it’s all down to Etienne’s paternalistic attitude, his repeated decisions to unilaterally remove agency from the women around him.

So in the end, I guess I do come down on the side of it being both relevant and interesting that the omnipath of the story is male, and that his most egregious manipulations are directed at women. To be clear, I don't believe that Etienne is being painted as an outright misogynist, but I would argue that even beyond his specific control of Eliza and Masumi, the instinct he has to suppress, control or outright banish emotion reflects a culturally-influenced distaste for emotional honesty and empathy, and a blinkered focus on (stereotypically masculine) stoicism and repression. When combined with his dedication to some kind of quantifiable ‘objectivity’ as lauded by the male philosophers he references, it doesn't exactly paint an encouraging picture (and I'm inclined to think the narrative agrees that it won't lead anywhere good in the long term).

And, of course, it can’t be ignored that if Etienne is mirroring Xavier, and Heavy is mirroring Magneto, then Masumi and Eliza seems to be gesturing in the direction of Dark Phoenix and the Scarlet Witch, characters whose mythos and treatment over the years is inexorably tied in with their gender. There’s a long and unsavoury history of female superheroes’ emotions and mental health being treated as a problem (an aspect, I’d argue, that explains why some people were affected so strongly by the Captain Marvel film’s otherwise entry-level feminism); many male heroes have had moments of being corrupted or taken over, but none of these incidents are embedded so wholly into their lore and the general cultural consciousness surrounding them as they are for the likes of Jean Grey and Wanda Maximoff.

Absolute power corrupts absolutely - if you’re unfortunate enough to be a female superhero. Whether the Power Fantasy succeeds in subverting or otherwise commenting on these parallels remains to be seen.

What about the other characters? I’ve covered Valentina already, but I’ll add that I do enjoy the thoughtful, solemn, reflective side she’s recently demonstrated when reflecting on her mistakes, and I’m interested to see where else the story takes her. She’s moral, but at this stage of the story, not as naive as she first appears. I'm looking forward to see how she develops.

As for Magus, he is, as has been painstakingly pointed out, a cult leader. To properly tackle that dynamic, he needed to be a man.

I think a female Heavy would have been interesting. (Very interesting, in terms of Kid Ignition, and raising a son that you hope will continue to listen to you, respect you, and follow your ethics.) But he, too, is a cult leader of a different kind, and his braggart ‘eye for an eye’ attitude to world politics reflects a certain toxic masculinity that would, again, come off very differently if he were not male.

With all this said, Eliza and Masumi’s present condition is still a tiresome and uncomfortable status quo for anyone who enjoys their female characters with agency. I’m eager to see it interrupted, however cataclysmic that might be for the rest of the characters in the story. And while I am deeply enjoying what the Power Fantasy has to say about power, and about ethics, and about relationships, I’m still waiting to be fully convinced that the underlying gender dynamics are quite so thoughtful.

1. I’m very conscious that I’m complaining that my personal power fantasy is not being catered to by a comic about the dangers of power that knowingly, winkingly calls itself The Power Fantasy, but it’s not that I want to see women girlbossing, it’s that I want them to have the same nuance and agency in how they interact with the world that any of the men do. ↩

2. Etienne's lack of succession planning, so to speak, is… interesting. He moves through the world as if he will never die, and he's too clever to not have considered the dangers of making himself the sole point of failure in so many areas. He's already intimated that he can't be killed that easily; what that means in practice remains to be seen. ↩